I knew that if I was going to write a book about J.S. Bach’s family life I would need to go back to the start and hunt down his earliest influences and experiences. Like any good music student, I could recite that, “Johann Sebastian Bach was born in Eisenach in 1685,” but it struck me how little I knew about that town, that year, and those people to whom he was born. My daily work teaches me, however, that origins are an important part of every father’s journey, whether they offer negative memories to confront or positive ones to build upon.

The process of slowing down to understand Bach’s formational home environment gave me the material for my first two chapters on his birth and childhood as the youngest son of a Town Musician. It also provided several rabbit trails into other perspectives on Bach and his times, which—this being a personal passion project—I was happy to follow. One trail led to months of reading on the Thirty Years War; a bloody human tragedy that raged around Bach’s musical ancestors for multiple generations. Another, which may or may not feature in the book, calls upon my lifelong love of the woods.

Though most musicologists tend to find little of interest between Bach’s birth and the start of his formal education, I found myself pausing, among many places, at his Baptism at St. George’s Church. Two godfathers are listed: Sebastian Nagel, a neighboring Town Musician, and Johann Georg Koch, referred to in the registry as, “the Ducal Forester of this place.”1 One of his godfathers was the duke’s forester? What was forestry even like back then? I wondered.

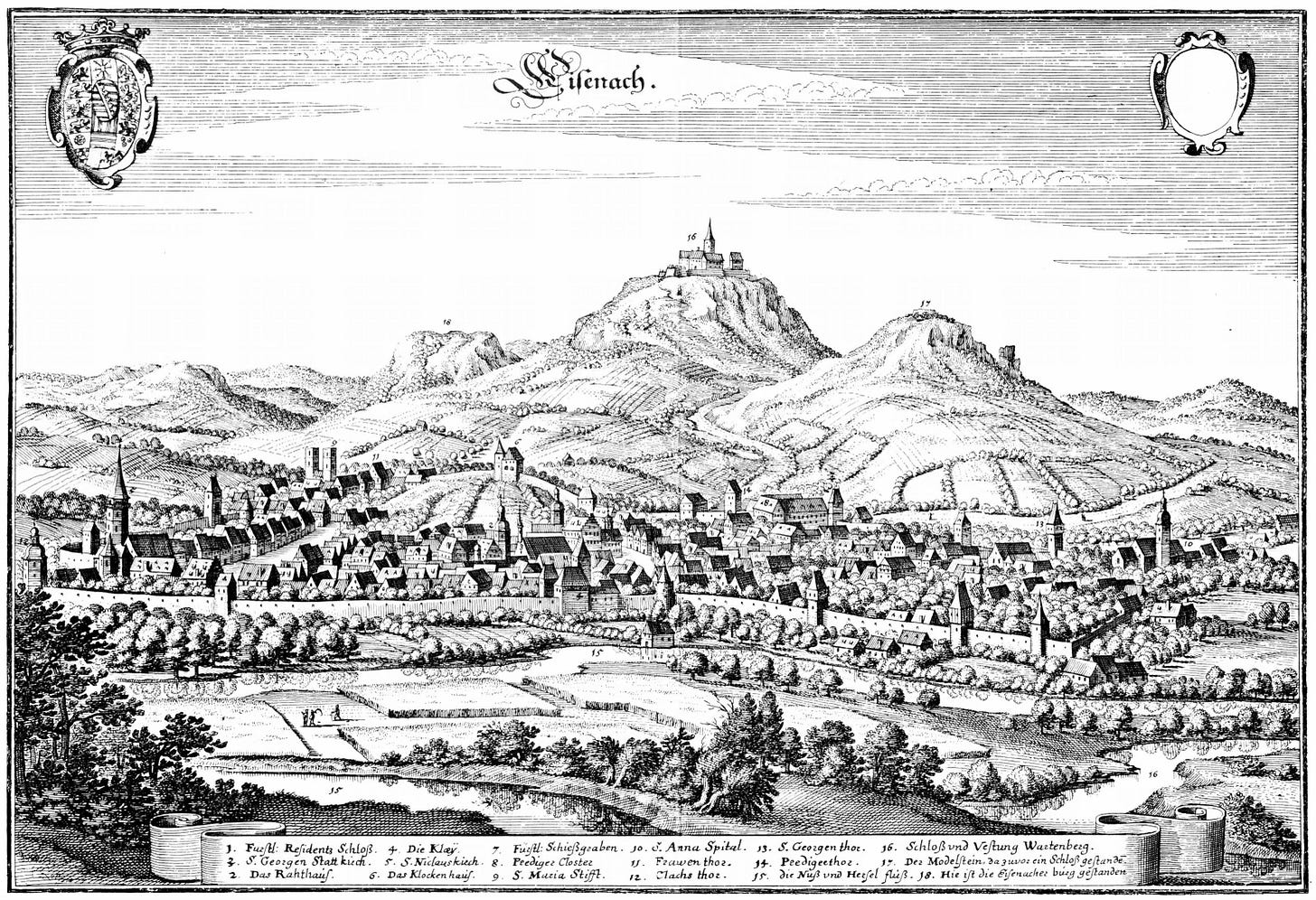

Baby Bach’s father Ambrosius was in charge of daily music for the town of Eisenach, but daily food and firewood were also needed, having to be managed despite the recent environmental devastation of the Thirty Years War. I learned, after some digging, that German forestry had some of its earliest developments during this time period, beginning a long recovery that would eventually earn the state of Thuringia the affectionate title of “the green heart of Germany.” A drawing of Eisenach from 1647 shows more farmland than we see today, which would have been leased out to farmers by the Duke, but trees also, which would have had a few decades to multiply before Bach’s birth.

Today’s classical musician, despite practicing on a wooden instrument all day, may not often think about the necessity of natural resources, nor do many fully understand where their food comes from. Life was less compartmentalized in past centuries, however, so we find that Bach’s father was friends not only with other musicians but also with other important town employees like the forester. Sebastian, as he was called, grew up with these everyday influences and remained proud of his hometown, keeping “of Eisenach” in his title throughout his life though he would only spend his first decade there.

Christoph Wolff, the distinguished Bach scholar, makes a compelling case for seeing Bach as a “musical scientist” who, like Sir Isaac Newton, brought us new understanding of the natural world by imitating it and pointing, even bridging, to its Creator. “For Bach,” Wolff says, “art lay between the reality of the world – nature – and God, who ordered this reality.”2 Toward this end, what better place could Sebastian have spent his formative years than Eisenach, a town rich with Protestant history and surrounded by forests and mountains?

My brothers and I also grew up in a small town in the countryside, spending half of our childhood studying the creative arts and the other half roaming the woods and fields. From building forts to filling sketchbooks with our drawings of plants and animals to learning how to hunt and process deer with our dad, the forest and its fruit were essential in the development of our creativity. We listened to Bach’s unaccompanied sonatas and partitas surrounded by the smell of fresh wood shavings in our workshop and brought our violins on an annual group hunt to play for our fellow hunters around the crackling fire in the lodge. For these dear friends, hunting was all about communion with nature, and our music landed well on ears so accustomed to listening. At 14, the age I started soloing with local orchestras, I also apprenticed to a bowyer, building custom longbows for traditional archers and hunters.

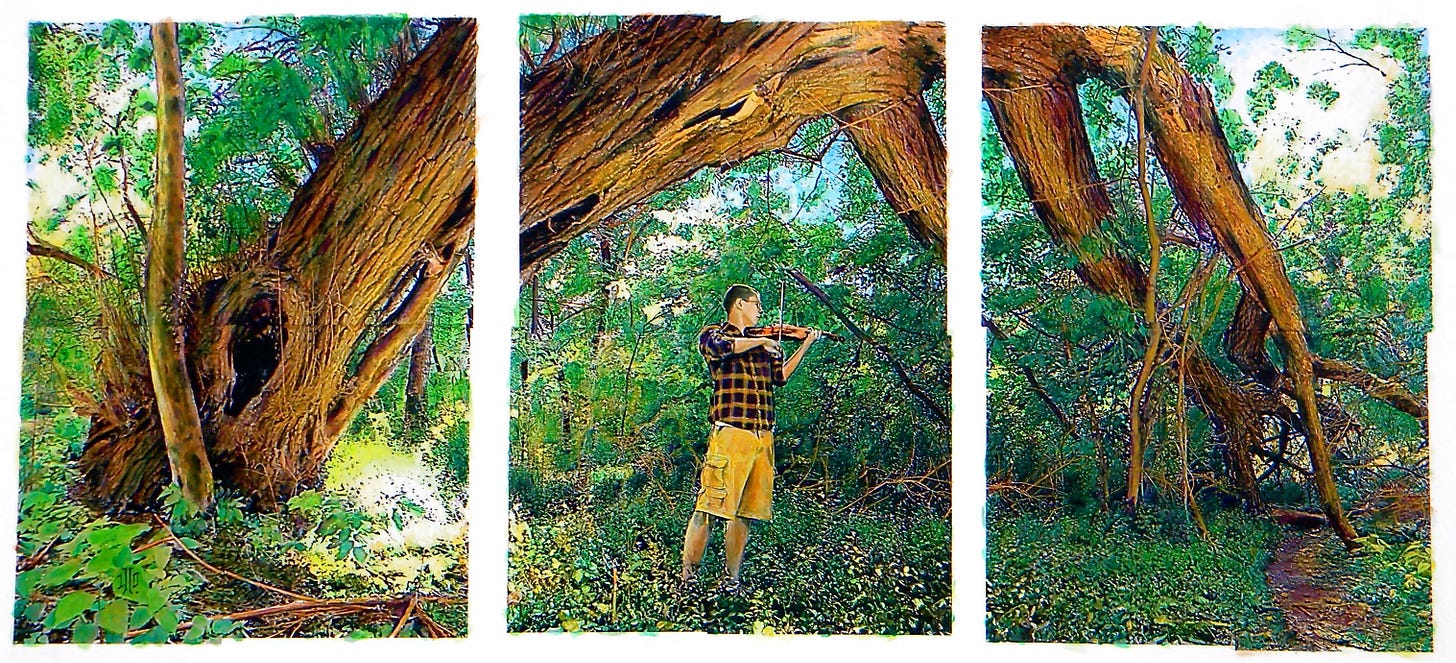

My freshman year of college in the city felt claustrophobic; my study of music restricted by the white walls of drab practice rooms rather than fed by the natural beauty of the woods in which I had grown up. For me, nature and art could not be delinked and lead to anything truly beautiful. This led to a feature-length article I wrote during my sophomore year titled, “Bowhunting and Classical Music… A Funny Mix?” highlighting several crossovers between the two disciplines in my life and throughout history. I was delighted that my findings were championed both by my music history professors at Carnegie Mellon and by the bowhunting community, with the article being published in Traditional Bowhunter Magazine. An artist friend loved the theme as well and painted a triptych of me playing violin in the woods.

Just as my brothers and I were not the last classical musicians to benefit from time in the woods, neither were we the first to bring violins to a hunting lodge. Bach too celebrated the “lively hunt,” performing his secular cantata Was mir behagt, ist nur die muntre Jagd! BWV 208 at the ducal hunting lodge during one of his first jobs. Amid lighthearted arias and recitatives about hunting as the delight of gods and heroes, we gain one of Bach’s most famous melodies, “Sheep May Safely Graze,” which reflects the peace and rest that comes when a good shepherd—or just ruler—stands watch.

Trees surrounded Sebastian not only during his early years in Eisenach or his gigs at the ducal hunting lodge, but also on the roads he walked to hear and study music, first alongside his brothers and eventually with his sons. Many journeys we know he took through the Thuringian countryside would put many of our wilderness adventures of today to shame. The healing solitude that causes us to build hobbies around such things as hiking and hunting was, for the Bachs, a natural part of life and its transitions.

I loved James Runcie’s recent novel called The Great Passion, in which he portrays Bach as a real human; both dogmatic in his faith and tender with his family and students. In one moving chapter, the Bach family takes an afternoon to break away from the rigorous schedule at St. Thomas School in Leipzig for a peaceful walk in the woods to hunt for mushrooms. It is a picturesque outing in its own right, but also features an unforgettable moment of raw fatherly care. When one of the young sons goes missing, the family searches until dark and finally finds him having hurt his shoulder falling from a tree. Runcie writes:

When the Cantor arrived, he slid down heavily on to the ground and pulled his child close to him, getting mud, leaves and bracken all over his coat. ‘My son, my son, you’re safe. All is well. Nothing is wrong. Praise God that you can speak. Praise him, praise him.’

I believe Runcie was wise to include this scene, taking Bach from his composing room back to the basic woodland elements that accompanied his childhood, reminding him and us there of what is most important in life: the flourishing and safety of our loved ones. Bach is like the shepherd who rejoices when he finds his lost sheep, caring no less because he has others in the fold.

Looking out for Bach’s time in nature is one of many ways I am finding deeper appreciation of his polyphonic life, helping me gain a richer picture of his life with his family. Sebastian’s grandson and namesake, Johann Sebastian Bach “the Younger,” son of the composer C.P.E. Bach, became an impressive landscape painter. The young artist’s surviving works show a special devotion to trees as glorious backdrops for everyday life, as in the one below of a young bowhunter and his dog. I will leave you with this painting and a quote about the forest from another great German composer, Ludwig van Beethoven: “My miserable hearing does not trouble me here. In the country it seems as if every tree said to me: ‘Holy! holy!’—Who can give complete expression to the ecstasy of the woods! O, the sweet stillness of the woods!”3

Wolff, Mendel, and David, The New Bach Reader

Wolff, Johann Sebastian Bach: The Learned Musician

Kerst and Krehbiel, Beethoven: the man and the artist, as revealed in his own words

I’ve recently been enjoying BWV 88 Siehe, ich will viel Fischer aussenden, which has musical and textual references to fishing and hunting throughout.